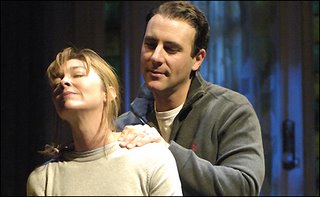

Donna Bullock and Jordan Lage in Rabbit Hole

Grief is a house of many rooms, several of which slide across the stage in David Lindsay-Abaire’s affecting Rabbit Hole, now in its local premiere at the Huntington Theatre. Critical reaction to the show slid back and forth, too; the Herald found it “void of heart,” while the Globe, in stark contrast, felt its weight of emotional pain was “almost unbearable.” The Phoenix split the middle, calling it “poignantly acted” yet “nicely manicured.” There was a general feeling that the author (a Southie native) had tiptoed up to the sentimental verge of television drama, but not gone over the edge (one web critic, however, offered a single-sentence review: “Rabbit Hole is television-as-theatre.”). The critical consensus on television writing versus stage writing, of course, has yet to be reached, but in the meantime some commented on the shift in tone that Rabbit Hole represented for Lindsay-Abaire, whose previous works were the surreal Fuddy Meers and Kimberly Akimbo; with Rabbit Hole, as the Phoenix quipped, it seemed that “Craig Lucas had gone to bed and awakened as David Margulies.”

But none of these critics seemed able or willing to grapple with the structure or intent of the work itself; several sniffed at its resemblance to “Lifetime drama” while naively critiquing it solely in terms of - yes - Lifetime drama, a case of cognitive dissonance if ever there was one. In fact, as witty as the Phoenix quips were, its critic missed the salient point about Rabbit Hole; the play’s structure still quietly echoes the surreal anatomy of Fuddy Meers and Kimberley Akimbo, only this time disguised as metaphor.

For Lindsay-Abaire’s conceit is that grief operates in something like the many-worlds mode of quantum mechanics (where probability rules) and string theory (which depends on parallel universes). His characters – a yuppie couple who lost their child in a car accident – don’t literally vanish down a wormhole with Steven Hawking, of course; they are, instead, locked in a cycle of bereavement as they slide down “rabbit holes” into new versions of their grief. The trigger can be anything – a random comment, a rediscovered sneaker, a video that’s been recorded over – but, like a collapsing wave function in some physics lab somewhere, their grief suddenly comes back into sharp focus, in a new, parallel world-of-shit right next to the old one. The process is largely fed by issues of causality and blame. Who is responsible for the little boy’s death? The teenager who “may have been” slightly speeding down the street? The parent who for a moment wasn’t watching the front yard? Or perhaps even the dog the child was chasing?

Or is no one to blame – meaning that no one need suffer retribution, but also that no one can work toward redemption? This is the deep chill that suffuses Rabbit Hole – and one that has all but frozen mother Becca (Donna Bullock) in her grief, because there is simply no thread of meaning to lead her out of it. For Becca, moving on will require eliminating not just her son’s death but his very existence from her life; thus we see her cleaning out his toys and clothes, then demanding that the house be sold, and then even “accidentally” erasing a videotape of him. Meanwhile her husband, Howie (Jordan Lage) seems at first healthier, if more sentimental, in his grieving process; he clings to memories of his little boy, while already thinking about having another. But Becca insists he’s not “in a better place,” just “a different place” (those parallel universes again), and indeed, when Howie unexpectedly runs into the boy who accidentally killed his son (Troy Deutsch), we can see from his buried rage that, indeed, he really hasn’t gotten past anything at all.

Yet this gawky young teen (convincingly impersonated by twenty-something Deutsch) unexpectedly provides the key to Becca’s parallel prisons. His take (or maybe toke?) on the multifoliation of time and space offers Becca a sense of equipoise that, in turn, makes her trips down the rabbit hole less harrowing – for perhaps in some parallel universe, her little boy never ran into that fateful street, and that car never swerved.

Whether this slim “Tao-of-Pooh”-like reed is strong enough to serve as the crux of the drama (or is, instead, just another kind of pooh) is debatable; I tend to think the author has dodged the requirements of his climax, which should have included a confrontation - and renewed connection - between Becca and Howie. This failure, however, hardly dims the power of much of what has come before – Rabbit Hole is about as accurate a guide to grief as one is likely to find, and director John Tillinger has guided his capable cast through its anguished arc superbly. The supporting cast is particularly strong - Geneva Carr, in particular, all but nails Becca’s friendly floozy of a sister, who has thoughtlessly gotten pregnant just as her sister is dealing with death (another parallel, in a way). Maureen Anderman, meanwhile, is slightly miscast as Becca’s trash-talking mom (Anderman’s just too sveltely high class for the role), but has clearly worked her way through the character in an amusingly blunt-yet-scattered style (it turns out she lost a son, too, in yet another – well, you get the idea). Meanwhile, at the center of the drama, Jordan Lage and Donna Bullock manage to quietly keep their balance, both against each other and the conflicting requirements of the play. Like Anderman, however, Bullock is slightly miscast – she hasn’t been able to scrub all the glamour from her persona, and she’s a little too self-controlled to tap into the obsessive fear that must underlie Becca’s anger. Lage is actually more skilled at the fine art of emotional collapse; both his Act I breakdown and his Act II slow burn are among the best stretches of acting seen in Boston this year.

The physical production, as usual for the Huntington, is impeccable, although the point of James Noone’s sliding set seems to have been lost on many. (Perhaps the slowly rolling “worlds” are almost more trouble than they’re worth.) Elsewhere director Tillinger hints at the metaphysical (over the central staircase night-time shadows play that might belong to Becca – or someone else), but for the most part hews closely to the play’s naturalistic surface. This isn’t fully satisfying – but then, it’s hard to pinpoint exactly where it goes wrong, either. Perhaps Rabbit Hole is a transitional play for Lindsay-Abaire, a step towards a new synthesis of the real and the surreal - or then again, perhaps it will be remembered as merely an odd cul-de-sac in his burgeoning career. It certainly is not a wholesale leap from one dramatic universe to another, much less a step down from the stage to the small screen. But whatever its long-term import, it retains its power to move us; Mr. Lindsay-Abaire is a genuine writer for the stage, and Rabbit Hole is a genuine contribution to it.

No comments:

Post a Comment